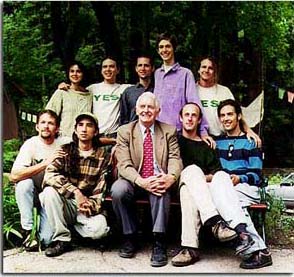

A Chat with David

R. Brower

"A

Few Suggestions for Young Leaders"

[excerpts from an interview in 1997]

At 87, David Ross Brower still hasn't toned down his

sense of vigor. After starting Friends of the Earth, Earth Island Institute

and the League of Conservation Voters, you'd think he'd retire. But this

was not to be.

As the first director of the Sierra

Club in the 1950s, Dave became a visionary for the world's conservation

movement and remains an inspiration today to those who care about ecology.

He is

one of my most treasured friends.

Wiliam Buck: Do you still consider yourself a youth?

David Brower: Yes. I consider myself a very young 85.

WB: When you first met Ansel Adams, you were only 21 years-old. You've obviously been committed as an activist since you were very young and you've made it this far. What was it that helped you stay active for so long?

DB: The thing that bothers me about this civilization now

is, I guess in our education system and wherever else, there's this sense

of wonder which comes into every child and there seems to be this great

urge to smash it, to get rid of it. Let's not.

One of my sound bites is "Nothing succeeds like succession."

That's what's going on in nature. It's a flow, a constant flow.

Different things are happening all the time. There's no point in

trying to stop the clock, the point is to keep things running and watch

what happens as things develop. That's the excitement. If

you haven't been given something to wonder about yet, have a look again

tomorrow and check what you thought had already been solved.

WB: Or "Call Dave!" Do you mind if we print your number, just in case a young leader needs some advice?

DB: No, call me. But don't expect me to answer a letter, I haven't learned how to do that yet.

WB: What advice do you have for young people active in today's environmental movement?

DB: Get out of the country! Get out of the country

and don't go there to see how great we are, go there to see how great

they are and what they've remembered that we've forgotten. Primarily,

in so-called developing countries. This is the thing I would like

to remind young people of.

Don't stay too long and don't wear out your welcome. But I don't

think you will if you don't try to be the "ugly American" or

the "ugly-developed-country-person" who has all these "things"

but has lost a certain amount of spirit. What's happening to us?

We think we have all these advantages but something is just missing very

much in our lives. The attempt to get more happiness is not showing

up. We're getting more hopelessness, not more happiness. This

is partly from what we've been doing to the Earth.

WB: What are some other steps you think young folks could take to become more sustainable as activists in the movement?

DB: I'm very anxious for everybody to listen to what Father Thomas Berry said: "We should put the bible on the shelf for 20 years and read the Earth." Think about that, "read the Earth". It's an extraordinarily beautiful thing to read and it's hard to understand and we never will understand all of what's going on. It's the challenge of trying to figure it out a little more. Just to look out there, whether you're looking at a leaf or watching a bird.

WB: One of the things about our friendship that really inspires me is that neither of us has lost his sense of wonder. How have you retained your sense of wonder for 85 years?

DB: There's just so many things to look at. I've just had

a lot of experience getting into places where the wonders you're looking

at are natural. Over billions of years, nature has been figuring

out how the hell to run this planet and it's done a pretty good job.

We haven't done that good a job and I'd like to get back out to see, well,

what's it look like when it's done right?

My parents gave me a fair break, and I learned from that to give that

same thing to my children and to my friends. I have made a lot of

mistakes. But not nearly as many I could have if I'd tried harder.

WB: How is today's younger generation different from your generation at the same age?

DB: The Earth has been terribly wounded and too many things

have been used up; too much carelessness. We forgot to care and

when you don't care you get a substitute reaction: hopelessness; "There's

nothing you can do about it, it's inevitable." There's a line

that goes, "Inevitable? Not if we say 'No!'"

I love talking with young people, that's how I recharge my batteries.

I see the hope that should be there and I feel the obligation of doing

what I can do at my advanced age, doing some "downfield blocking"

or whatever it is, to help make it possible for them to have the experience

I had. I have this simple-minded example from my own life, growing

up and doing wilderness trips in the Sierras. I could camp anywhere

I wanted to camp, there was plenty of firewood, and you could drink the

water anywhere. All those are gone. And it was an unnecessary

loss, we're not quite aware of losing it and I'm just anxious that we

not lose anymore and we start to build back.

WB: How do you think young people should deal with the legacy that has been left them?

DB: I think there's a very big obligation on the older

people, all of whom have been young once, and have tended to forget

it. It's not easy out there. Right now, particularly.

It's so different.

This is what happens when you have exponential growth. It's a very

slow growth at first, you just go along the floor, slighty increasing.

But when you get exponential, you start going up the wall. And you're

going up the wall faster and faster, depending on the existence of things

that are used up. You can't do it again.

Our institutions aren't awake to this yet. And this is one of the

things I'd like to see young people say: "Hey, wait you guys.

You used it up. And we've got to use a different approach.

And we're going to need your help."

There are pretty damned unhappy consequences from our over-use, our over-spending

of the legacy.

WB: Well, to lighten things up, what do you think about the idea of having fun?

DB: Well... I do believe in fun.

One of our [David and his wife Anne's] favorite writers, Lauren

Eisley, came up with this line I particularly like: "We are compounded

of dust and the light of a star."

Quite powerful lines. And when you get to be 85, you realize, well,

no one is going to be permanent, and the dust is going to have other uses.

My line is "I hope whoever gets my dust next time has as much fun

with it as I did."

I've had a hell of a lot of fun, primarily through my experiences with

other people, doing this work.

copyright © 1997 William R. Buck